Boosting product or service offering with optimized cost is a strategic objective of most manufacturing and service industries in the world. Nevertheless, tactics to achieve this objective range from shortsighted organizational downsizing and payroll cut to farsighted mindset of combating hidden costs. In the latter tactics, management exerts tight control over Cost of Quality (COQ) to achieve more with less while balancing the trilogy of profitability, customer, and employee satisfaction. Moreover, if inflated, COQ becomes a serious silent killer that eats profitability for breakfast. Hence, monitoring and controlling COQ is indispensable to survival.

What COPQ is and how it is related to COQ

Cost of Quality (COQ) and Cost of Poor Quality (COPQ) are sometimes erroneously used as synonyms to each other, whereas COPQ is actually one component of COQ. COQ-sometimes referred to as Total Cost of Quality- is the total costs associated with preventing failures, appraising quality level, and those costs resulting from failures. Hence, COQ comprises two main components; Cost of Good Quality (COGQ) represented by prevention and appraisal costs, and Cost of Poor Quality (COPQ) for failures costs. Failure costs are divided into External Costs (supply chain costs) and Internal Costs (field failure costs). Total COQ can be represented in the equation below:

A closer look into COQ Components

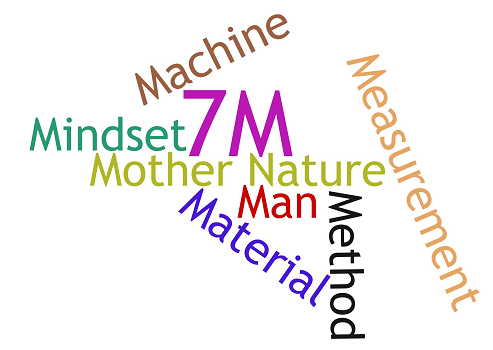

The key differentiator between Internal and External Failure costs is whether they occur before or after reaching the customer. Internal Failures are those resulting from products or services not conforming to requirements occurring before reaching the customer. Such might take place in any of the Design, Procurement, or Production processes. For instance, a rework-associated cost of a finished product due to design changes is an internal failure taking place before delivery to customer. Similarly, replacing defected raw materials acquired from a supplier is considered an internal failure cost happening during the procurement process.

On the other hand, External Failure costs are those costs incurred by products or services not conforming to requirements occurring after reaching the customer. 2009 Toyota’s recall of vehicles due to unintended acceleration is a perfect example of external failure that caused 52 deaths, 38 injuries, and a financial loss of USD 5.5 billion. Another tragedy depicting an external failure is the historical 1986 space shuttle Challenger explosion that happened 73 seconds after takeoff leaving 7 deaths and a financial loss of more than USD 1 billion.

On the other end of the spectrum exists the good COQ that if leveraged will combat the poor quality costs. Despite being cost, Appraisal and Prevention activities are desirable to a certain extent beyond which the law of diminishing returns dominates. Raw materials receiving inspection, for instance, will decrease the odds of having nonconforming input to the manufacturing process (Appraisal activity). Even better, going the extra mile in reviewing and rating your suppliers regularly would increase the odds of receiving consistent quality items which could even spare you frequent receiving inspection down the road (Prevention activity).

In spite of the fact that Appraisal costs are considered good COQ, they better be used wisely. This is because they are detective rather than preventive activities. For example, inspection of a finished product at the end of the line would probably detect defects, but will never eliminate the root causes; so, defects recur. Hence, Appraisal costs are costs incurred to determine the degree of conformance to quality requirements not to prevent causes of failure. This component of the COQ can take place anywhere during procuring raw materials, producing an item, or could be in activities external to the organization such as inspections, tests, or audits conducted at the site for installation or delivery.

Prevention costs is the other part of the Cost of Good Quality, and it is the best to maximize in the equation as they keep Failure and Appraisal costs to a minimum. They are costs of all activities designed to prevent poor quality in products or services. It has been pointed out that cost to eliminate a failure after delivery is five times that at the development or manufacturing phase. Therefore, prevention activities are best performed at upstream rather than downstream processes. For instance, reviewing a design before release to manufacturing would spare the organization extra costs that might be incurred due to internal or external failures after production. Prevention activities might be deployed anywhere in the value stream starting by Marketing throughout Production.

Optimizing Total Cost of Quality (TCOQ)

Going back to the TCOQ formula mentioned above, logically yet still controversial, the TCOQ value cannot be zero. It is rather an optimization problem. Unless operates in a perfect world, any organization can never produce or offer a defect-free product or service without deploying appraisal or prevention measures. Obviously, Cost of Good Quality (COGQ) components, Appraisal and Prevention costs, need to be maximized, whereas Cost of Poor Quality (COPQ), Internal and External Failure costs, are to be minimized so as to reach to the minimum TCOQ value.

As shown by the figure above, COPQ declines as the Quality Level improves, but this doesn’t occur without exerting some level of prevention efforts. The key question that the TCOQ formula should answer is “to what extent should the organization invest in COGQ so that it reaches the minimum TCOQ with the optimum quality level of the product or service?” And the answer points to where the organization needs to position itself consistently to retain competitiveness or, more bluntly, to survive.

Improving a product or service quality level while keeping profitability at decent levels is not a walk in the park endeavor. However, having a proper grasp of the Cost of Quality concept and methodology coupled with a standardized approach of monitoring and controlling over optimum levels of cost allow the organization to balance the competing demands of profit, customer and employee satisfaction.